|

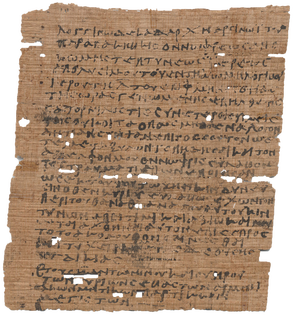

Like today, people in the ancient world dealt with all sorts of crime, violence, rape, murder, theft, and so on. In many cases, crimes in the ancient world were never reported. And we can understand why: rural settings usually lacked protection against crime and violence. And this is precisely one of the reasons travel in the ancient world was considered dangerous. Someone could mug you and steal your garment and easily get away with it. Think about it. No one is around to help you or to witness the attack, and so you sit there wounded, hoping that a good samaritan will pass by and help tend to your wounds. It's no surprise, then, that Jesus' parable of the good Samaritan in the Bible was so effective: people knew exactly what he meant! But in some cases, violence was indeed reported. We have many papyri from Roman Egypt documenting such cases. Last week, for example, I posted on a case of domestic violence in a fourth century papyrus, where the wife sought the protection of the Roman state against her violent husband. Another example is P.Tebt. 2.304, a second century petition concerning an assault on Pakebkis and his brother Onnophris in the ancient Egyptian town of Tebtunis. Here is the text:

The "well-known temple" is a reference to the temple of the crocodile god Soknebtunis ("Sobek, lord of Tebtunis"), which the local inhabitants worshipped. In fact, many of the papyri discovered in Tebtunis were found in the papyrus wrappings of mummified crocodiles (though not this one, which was discovered in a house of the town). We learn from the papyrus that Pakebkis (and presumably his brother Onnophris also) was a priest in this famous temple. The petition describes a violent gang attack upon the two priests, which was apparently instigated by a ringleader named Satorneilos. The attack, which happened at night, was apparently so brutal that Onnophris suffered life-threatening injuries. Pakebkis wanted justice and so he appealed to the state for help. The petition itself is customary: it is addressed to an official (in this case, the decurion, an official responsible for criminal offenses), describes the event, names the attacker, and requests that the state arrest Satorneilos and bring him to trial. Pakebkis could have written this petition himself. The sloppy handwriting might support this. The other possibility is that Pakebkis did what most everyone else would do in such a situation: he went down to the local scribe, told him what kind of legal document he needed, and described the attack. The scribe would in turn draft the petition, make a couple copies, and give it back to Pakebkis, who would then either take it directly to the office of Longinus, or have it sent to him by way of a letter-carrier. It was then up to the state to respond.

Legal documents like this one are fascinating because they allow us to see the kinds of crime that took place in the ancient world. From the perspective of social history, these papyri are interesting because we get to learn about real individuals who suffered these crimes, their occupations, their relationships, their desires for justice, and so on.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Available at Amazon!

Archives

June 2020

Categories

All

|