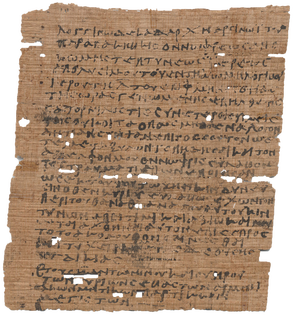

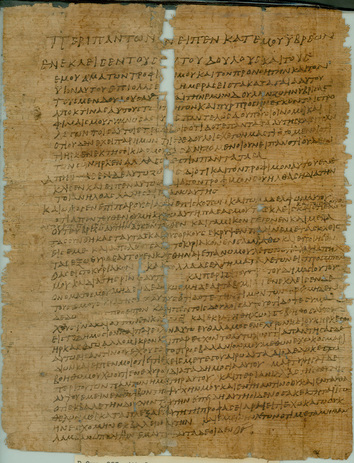

But in some cases, violence was indeed reported. We have many papyri from Roman Egypt documenting such cases. Last week, for example, I posted on a case of domestic violence in a fourth century papyrus, where the wife sought the protection of the Roman state against her violent husband. Another example is P.Tebt. 2.304, a second century petition concerning an assault on Pakebkis and his brother Onnophris in the ancient Egyptian town of Tebtunis. Here is the text:

| "To Longinus, decurion of the Arsinoite nome, From Pakebkis, son of Onnophris, from the town of Tebtunis, a priest, expempted from taxes, of the well-known temple in that town. On the 30th of the month of Epeiph, when it was late at night, a certain Satorneilos, along with many others—I know not why—did irrational violence to me, to such a degree that they attacked me with rods. They grabbed my brother Onnophris and wounded him, and as a result he is in danger of losing his life. Therefore, lord, since I am being cautious about his deadly condition, I submit this petition asking that you order him to be brought before you so that what is fitting transpires and I can receive the necessary satisfaction. Year 8 of Antoninus and Verus, lords, Augusti Armeniaci Medici Parthici Maximi." |

Legal documents like this one are fascinating because they allow us to see the kinds of crime that took place in the ancient world. From the perspective of social history, these papyri are interesting because we get to learn about real individuals who suffered these crimes, their occupations, their relationships, their desires for justice, and so on.