Friends and colleagues of mine often ask me if I use some kind of Bible software for biblical language study such as Logos or Accordance, the two most popular Bible software programs. Well, the answer has always been no. I am an advocate of learning ancient languages the hard way: by memorizing paradigms and various forms, and referencing lexicons and reference grammars. Call me old fashioned, but I believe this is the best way to learn.

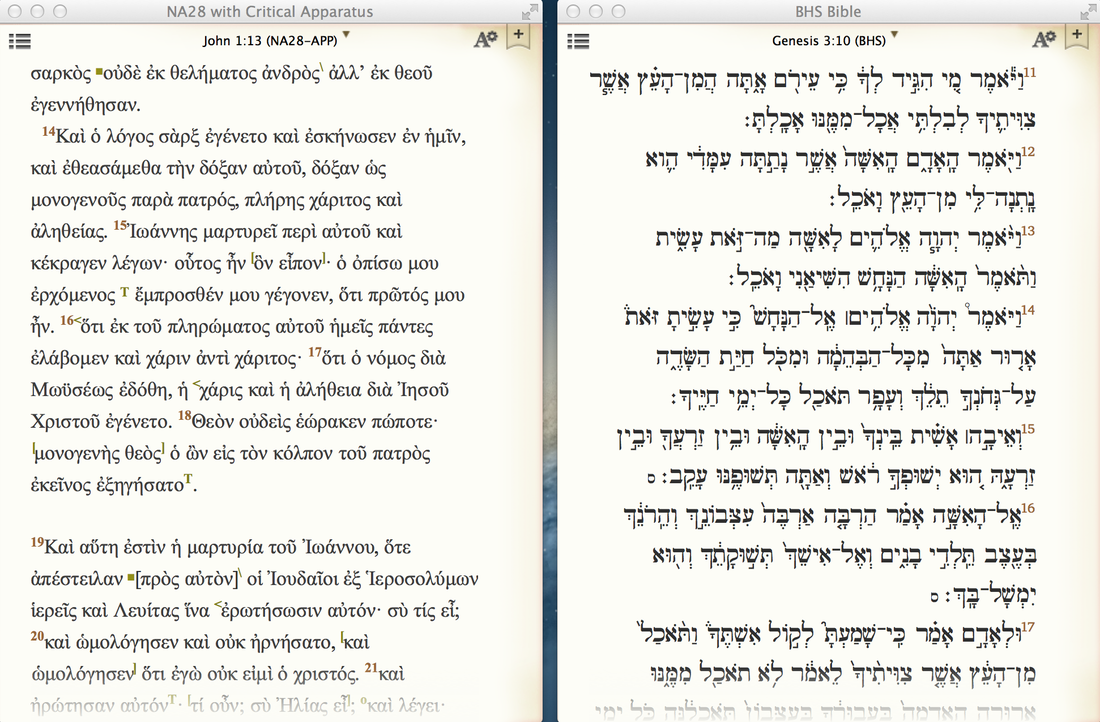

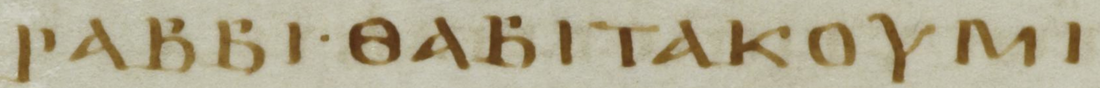

But for years I have used a fascinating program called Olive Tree and I want to review it briefly here. For whatever reason, most of my friends do not know about Olive Tree, but if you are looking for a program that will sync the NA28, BHS, LXX, English versions, NT and OT commentaries and much, much more on your Mac, iPhone, iPad, Android—then you should consider Olive Tree. When I am doing research, Olive Tree has been one of the most useful resources for me, because I can have all of my primary texts right in front of me on my computer, phone, or tablet. Hands down, I believe Olive Tree has all other programs beat when it comes to aesthetics and design: it is clean, crisp, and elegant. If you are working on a Mac, the desktop version of Olive Tree feels and looks amazing. It is even better on a retina display! I purchased the NA28 w/ apparatus, the BHS, the LXX, and the NRSV. There is the option to purchase "tagged" versions of the Greek and Hebrew Bibles, but, of course, I did not buy those. You can customize fonts, font colors, backgrounds, adjust text margins, add bookmarks, copy/paste, and share passages on Facebook, Twitter, e-mail etc. right from within the program. Searching for terms or phrases is very simple, and all your notes are saved in the "resource guide." For the NA28, the signs used in the critical apparatus take some getting used to, but the apparatus as a whole is very well designed and accurate.

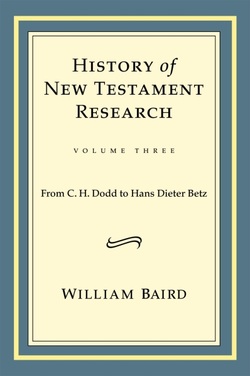

Olive Tree also has a very large database of academic commentaries that can be purchased individually or in bundles, such as: the Word Biblical Commentary (WBC), New International Commentary on the NT and OT (NICNT and NICOT), New International Greek NT Commentary (NIGNTC), Baker Exegetical Commentary on the NT (BECNT) among many others. There is also a large selection of academic books, lexicons, and other resources, such as: Theological Dictionary of the NT (TDNT), Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the OT (HALOT), BDAG, Eerdmans Exegetical Dictionary of the NT (EDNT), Bruce Metzger's Textual Commentary on the Greek NT (2nd ed.), and many others. There are also quite a few non-academic books written by conservative evangelical pastors (e.g., John McArthur, John Piper, Max Lucado) as well as books on apologetics and Christian living, which are of less use to academics. Nonetheless, Olive Tree is to be commended for providing this excellent program (which has actually been out for years) and making so many valuable resources available at the tip of the finger or mouse.

I would hope for two things. First, I would very much like to see Olive Tree incorporate a Sahidic Coptic New Testament like the one by J. Warren Wells, which Logos and Accordance have for purchase. Coptic is taught worldwide in many Universities and Seminaries today because of its importance for understanding Egyptian Christianity and its relation to the Greek New Testament. Thus, a Coptic NT would be a valuable addition to Olive Tree's database of resources. Second, I would like to see Olive Tree increase their selection of academic books on biblical studies. While there are quite a few academic books related to the Bible on their site, it would be nice to see Olive Tree add more, since their software is faster and more seamless than their competitors.

Realizing that I have a very wide readership, I would like to close by encouraging everyone to give Olive Tree a try. Visit their website by clicking here, and download the free app for your iPad, iPhone, Android tablet, Android phone, Kindle Fire, Mac, or Windows PC. Here are some screen shots of Olive Tree's application on my Macbook (Note: images are slightly blurry because they are screen shots):

But for years I have used a fascinating program called Olive Tree and I want to review it briefly here. For whatever reason, most of my friends do not know about Olive Tree, but if you are looking for a program that will sync the NA28, BHS, LXX, English versions, NT and OT commentaries and much, much more on your Mac, iPhone, iPad, Android—then you should consider Olive Tree. When I am doing research, Olive Tree has been one of the most useful resources for me, because I can have all of my primary texts right in front of me on my computer, phone, or tablet. Hands down, I believe Olive Tree has all other programs beat when it comes to aesthetics and design: it is clean, crisp, and elegant. If you are working on a Mac, the desktop version of Olive Tree feels and looks amazing. It is even better on a retina display! I purchased the NA28 w/ apparatus, the BHS, the LXX, and the NRSV. There is the option to purchase "tagged" versions of the Greek and Hebrew Bibles, but, of course, I did not buy those. You can customize fonts, font colors, backgrounds, adjust text margins, add bookmarks, copy/paste, and share passages on Facebook, Twitter, e-mail etc. right from within the program. Searching for terms or phrases is very simple, and all your notes are saved in the "resource guide." For the NA28, the signs used in the critical apparatus take some getting used to, but the apparatus as a whole is very well designed and accurate.

Olive Tree also has a very large database of academic commentaries that can be purchased individually or in bundles, such as: the Word Biblical Commentary (WBC), New International Commentary on the NT and OT (NICNT and NICOT), New International Greek NT Commentary (NIGNTC), Baker Exegetical Commentary on the NT (BECNT) among many others. There is also a large selection of academic books, lexicons, and other resources, such as: Theological Dictionary of the NT (TDNT), Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the OT (HALOT), BDAG, Eerdmans Exegetical Dictionary of the NT (EDNT), Bruce Metzger's Textual Commentary on the Greek NT (2nd ed.), and many others. There are also quite a few non-academic books written by conservative evangelical pastors (e.g., John McArthur, John Piper, Max Lucado) as well as books on apologetics and Christian living, which are of less use to academics. Nonetheless, Olive Tree is to be commended for providing this excellent program (which has actually been out for years) and making so many valuable resources available at the tip of the finger or mouse.

I would hope for two things. First, I would very much like to see Olive Tree incorporate a Sahidic Coptic New Testament like the one by J. Warren Wells, which Logos and Accordance have for purchase. Coptic is taught worldwide in many Universities and Seminaries today because of its importance for understanding Egyptian Christianity and its relation to the Greek New Testament. Thus, a Coptic NT would be a valuable addition to Olive Tree's database of resources. Second, I would like to see Olive Tree increase their selection of academic books on biblical studies. While there are quite a few academic books related to the Bible on their site, it would be nice to see Olive Tree add more, since their software is faster and more seamless than their competitors.

Realizing that I have a very wide readership, I would like to close by encouraging everyone to give Olive Tree a try. Visit their website by clicking here, and download the free app for your iPad, iPhone, Android tablet, Android phone, Kindle Fire, Mac, or Windows PC. Here are some screen shots of Olive Tree's application on my Macbook (Note: images are slightly blurry because they are screen shots):