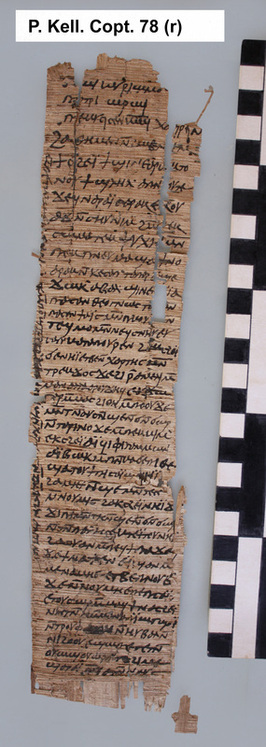

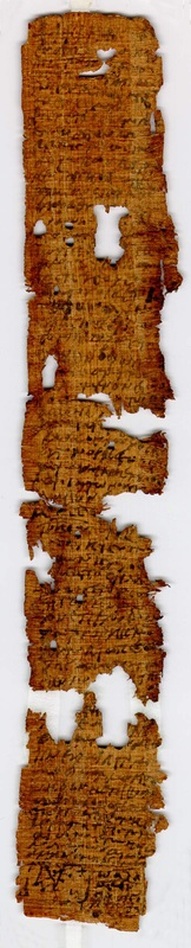

I have received some good feedback about these little manuscript "quizzes" so we'll keep them going until you all get bored! For this week, I have included a manuscript dear to my heart. This papyrus has been in my hands on more than one occasion. Note: this papyrus is not a continuous manuscript of the NT. So, which NT manuscript is this? What is interesting to you about this particular piece? Does anything odd stand out? Feel free to discuss or comment in the comments section below.

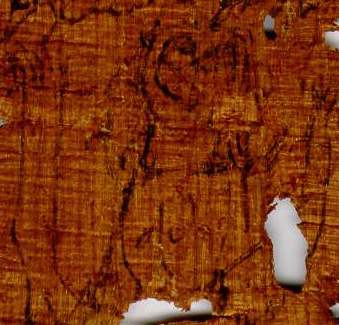

Update: So, several people nailed it on the head: this is P.Yale I 3 (P50). As I mention in the comments to this post, I had the privilege in 2010 of examining this papyrus on several occasions. For those interested in the knowing more about the strange lines on the first folio, see my comments below.

Update: So, several people nailed it on the head: this is P.Yale I 3 (P50). As I mention in the comments to this post, I had the privilege in 2010 of examining this papyrus on several occasions. For those interested in the knowing more about the strange lines on the first folio, see my comments below.