Over the last few years, I have quietly followed the productions and developments of the Green Scholars Initiative (GSI) and the Green Collection, along with the public statements made by those involved with their projects. Back in 2012, I raised questions concerning statements made by one of the former directors of the GSI, Scott Carroll, who no longer works in that capacity. Roberta Mazza has recently raised similar questions. In the post below, I provide some additional information about the Green Collection recently culled from the web.

In this video, Scott Carroll is interviewed on the Trinity Broadcasting Network, an American evangelical television network. Referring to a cuneiform tablet, the host says to Carroll, “I understand that our mutual benefactor, Jonathan Shipman, actually surprised you this very day and presented this [i.e., the cuneiform tablet] to you.” So, who is Jonathan Shipman? A Google search revealed Shipman’s Linkedin account. Apparently, Shipman was involved in acquiring at least some (if not most) of the Green items. He is president of Shipman Rare Books in Dallas, Texas, and, according to his Linkedin, he has “bought Millions of doallars [sic] in each area of these items also including Antiques and Antiquities, Have purchased over 7,000 Rare signature, From early Americana to early Greek, Syriac, Palestenian [sic] Aramaic, Arabic, and Coptic Papyrus writings of early known written things in the world.” His Linkedin continues: “A historian by research, not a schooled scholar of languages, but expert in the location to purchase of [sic] some of the rarest Books or objects sold in Modern times. Have traveled the globe in search of collections and objects helping lead to creation of several new planned Musuems [sic], and currently represent Museums, Private Collectors, Libraries, and other insitutions [sic] who desire similar things.”

But the Greens apparently cut ties with Shipman. In an interesting article on the Dallas Observer dated 23 August 2010, Jim Schutze reproduces two letters from the Green family indicating that they no longer were dealing with Shipman: “Please be advised that effective August 1, 2010, Mr. Johnny Shipman no longer represents the Green Collection, Mr. Steven T. Green or Dr. Scott Carroll, whether on behalf of the National Bible Museum or any other entity or organization.” The "National Bible Museum" was actually co-founded by Scott Carroll according to this website, and Shipman was the CEO. At least in March 2010, Hobby Lobby was "assisting the National Bible Museum," but by August 1, they had separated. So, what are the reasons for this split? And what are Shipman's sources for purchasing antiquities worth "millions of dollars"? Is the split with Shipman the reason why the Greens decided to establish their Bible museum in Washington D.C. instead of Dallas (Shipman's location), as previously planned?

On the personal website of Josh McDowell, an American evangelical Christian apologist, there is a very interesting post about an event called "Discover the Evidence," which took place on 5-6 December 2013. At this event, it is said that "each attendee actually participated in the extraction of papyri fragments [sic] from ancient artifacts. This had never been attempted with such a large group before. That was historic!" [NOTE: This quote has since been revised on Josh McDowell's site to the following: "We watched as papyri were carefully extracted from ancient artifacts. That was historic!"] The artifacts may be part of the collections amassed by Carroll, who was a main speaker at this event, since his bio at the bottom of McDowell's article states that "he and his wife have established both the Scott Carroll Manuscripts & Rare Books and a non-profit – The Manuscript Research Group, which provides access to scholars who identify and prepare for publication cuneiform tablets, papyri, Dead Sea Scrolls, biblical manuscripts and Torahs of enormous significance." So, apparently Carroll has now branched off from the Green Collection and Hobby Lobby to create his own collections under the auspices of the "Scott Carroll Manuscripts and Rare Books" and "The Manuscript Research Group." I am very interested in learning more about Carroll's organizations and the "Discover the Evidence" event and what took place there. What did the "extraction of papyri fragments [sic] from ancient artifacts" actually involve? Extraction from what? And why were (non-specialist?) attendees given hands-on access to unpublished artifacts? The article also mentions that "over 50 papyri fragments out of nearly 200 papyri that were discovered have been identified." 200 papyri? Where were they "discovered?" What is their provenance? Were these purchased by/via Shipman?

From all the videos and articles about the Green Collection (see, for example, this video featuring Carroll), it is clear that the antiquities are being used for apologetic purposes. Consider McDowell's statement about how the new manuscript "discoveries" will be used in this regard:

"These biblical manuscript fragments will be used of God to bring many young people to Christ. I plan to take these manuscripts, scrolls and masks with me as part of the Heroic Truth Experience to help provide an “a-ha” experience for young people and their parents, providing hands-on exposure to ancient evidence for the historical reliability of Scripture. Pray with me that these discoveries will be blessed of God to bring people to Christ and ground believers in the true faith so they can “give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have [in Christ]” (1 Peter 3:15, NIV). It will take several years to publish all these discoveries. We still have about 40 manuscripts to identify, who knows what else we will find?"

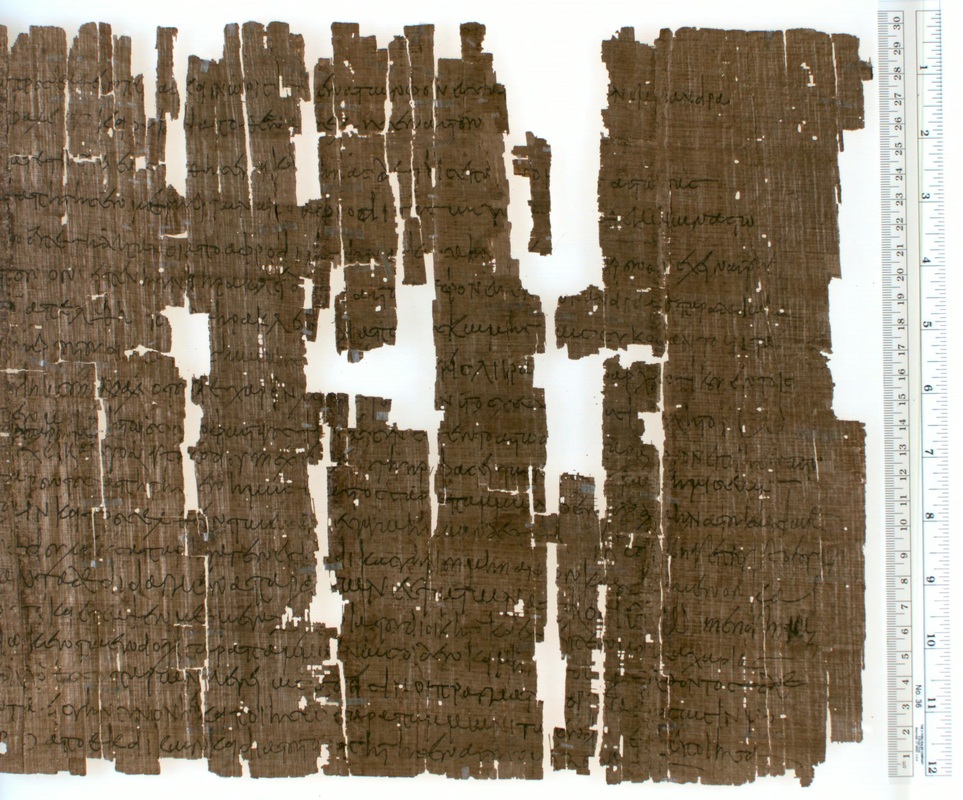

Some of the items in the Green collection are part of a traveling exhibition, which Roberta Mazza has just reviewed in light of her own visit to the Verbum Domini II exhibit in Italy. In Mazza's post, she makes reference to the Coptic papyrus of Galatians that I identified on eBay back in 2012. I gave an online "edition" of this papyrus on my old blog, and will soon migrate that post over to this site. On the basis of that edition, this papyrus was registered in the official list of Coptic New Testament manuscripts with the number "sa 399." It is interesting to hear that this papyrus is being featured in the exhibit. I would like to know more about the provenance of this item as well as others that may have been purchased off eBay by the Green Collection. It is hoped that these details will be clearly explained in the publication of such items, including the Coptic papyrus of Galatians, which is apparently "undergoing research" with the GSI.

The big questions that we are all interested in are: Where are these thousands upon thousands of antiquities coming from, all of a sudden? Who is involved in these transactions? What is the provenance of these cultural artifacts? Will the religious motivations behind the procuration and use of these items restrict academic study of them? I look forward to learning answers to these and similar questions over the coming months.

In this video, Scott Carroll is interviewed on the Trinity Broadcasting Network, an American evangelical television network. Referring to a cuneiform tablet, the host says to Carroll, “I understand that our mutual benefactor, Jonathan Shipman, actually surprised you this very day and presented this [i.e., the cuneiform tablet] to you.” So, who is Jonathan Shipman? A Google search revealed Shipman’s Linkedin account. Apparently, Shipman was involved in acquiring at least some (if not most) of the Green items. He is president of Shipman Rare Books in Dallas, Texas, and, according to his Linkedin, he has “bought Millions of doallars [sic] in each area of these items also including Antiques and Antiquities, Have purchased over 7,000 Rare signature, From early Americana to early Greek, Syriac, Palestenian [sic] Aramaic, Arabic, and Coptic Papyrus writings of early known written things in the world.” His Linkedin continues: “A historian by research, not a schooled scholar of languages, but expert in the location to purchase of [sic] some of the rarest Books or objects sold in Modern times. Have traveled the globe in search of collections and objects helping lead to creation of several new planned Musuems [sic], and currently represent Museums, Private Collectors, Libraries, and other insitutions [sic] who desire similar things.”

But the Greens apparently cut ties with Shipman. In an interesting article on the Dallas Observer dated 23 August 2010, Jim Schutze reproduces two letters from the Green family indicating that they no longer were dealing with Shipman: “Please be advised that effective August 1, 2010, Mr. Johnny Shipman no longer represents the Green Collection, Mr. Steven T. Green or Dr. Scott Carroll, whether on behalf of the National Bible Museum or any other entity or organization.” The "National Bible Museum" was actually co-founded by Scott Carroll according to this website, and Shipman was the CEO. At least in March 2010, Hobby Lobby was "assisting the National Bible Museum," but by August 1, they had separated. So, what are the reasons for this split? And what are Shipman's sources for purchasing antiquities worth "millions of dollars"? Is the split with Shipman the reason why the Greens decided to establish their Bible museum in Washington D.C. instead of Dallas (Shipman's location), as previously planned?

On the personal website of Josh McDowell, an American evangelical Christian apologist, there is a very interesting post about an event called "Discover the Evidence," which took place on 5-6 December 2013. At this event, it is said that "each attendee actually participated in the extraction of papyri fragments [sic] from ancient artifacts. This had never been attempted with such a large group before. That was historic!" [NOTE: This quote has since been revised on Josh McDowell's site to the following: "We watched as papyri were carefully extracted from ancient artifacts. That was historic!"] The artifacts may be part of the collections amassed by Carroll, who was a main speaker at this event, since his bio at the bottom of McDowell's article states that "he and his wife have established both the Scott Carroll Manuscripts & Rare Books and a non-profit – The Manuscript Research Group, which provides access to scholars who identify and prepare for publication cuneiform tablets, papyri, Dead Sea Scrolls, biblical manuscripts and Torahs of enormous significance." So, apparently Carroll has now branched off from the Green Collection and Hobby Lobby to create his own collections under the auspices of the "Scott Carroll Manuscripts and Rare Books" and "The Manuscript Research Group." I am very interested in learning more about Carroll's organizations and the "Discover the Evidence" event and what took place there. What did the "extraction of papyri fragments [sic] from ancient artifacts" actually involve? Extraction from what? And why were (non-specialist?) attendees given hands-on access to unpublished artifacts? The article also mentions that "over 50 papyri fragments out of nearly 200 papyri that were discovered have been identified." 200 papyri? Where were they "discovered?" What is their provenance? Were these purchased by/via Shipman?

From all the videos and articles about the Green Collection (see, for example, this video featuring Carroll), it is clear that the antiquities are being used for apologetic purposes. Consider McDowell's statement about how the new manuscript "discoveries" will be used in this regard:

"These biblical manuscript fragments will be used of God to bring many young people to Christ. I plan to take these manuscripts, scrolls and masks with me as part of the Heroic Truth Experience to help provide an “a-ha” experience for young people and their parents, providing hands-on exposure to ancient evidence for the historical reliability of Scripture. Pray with me that these discoveries will be blessed of God to bring people to Christ and ground believers in the true faith so they can “give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have [in Christ]” (1 Peter 3:15, NIV). It will take several years to publish all these discoveries. We still have about 40 manuscripts to identify, who knows what else we will find?"

Some of the items in the Green collection are part of a traveling exhibition, which Roberta Mazza has just reviewed in light of her own visit to the Verbum Domini II exhibit in Italy. In Mazza's post, she makes reference to the Coptic papyrus of Galatians that I identified on eBay back in 2012. I gave an online "edition" of this papyrus on my old blog, and will soon migrate that post over to this site. On the basis of that edition, this papyrus was registered in the official list of Coptic New Testament manuscripts with the number "sa 399." It is interesting to hear that this papyrus is being featured in the exhibit. I would like to know more about the provenance of this item as well as others that may have been purchased off eBay by the Green Collection. It is hoped that these details will be clearly explained in the publication of such items, including the Coptic papyrus of Galatians, which is apparently "undergoing research" with the GSI.

The big questions that we are all interested in are: Where are these thousands upon thousands of antiquities coming from, all of a sudden? Who is involved in these transactions? What is the provenance of these cultural artifacts? Will the religious motivations behind the procuration and use of these items restrict academic study of them? I look forward to learning answers to these and similar questions over the coming months.