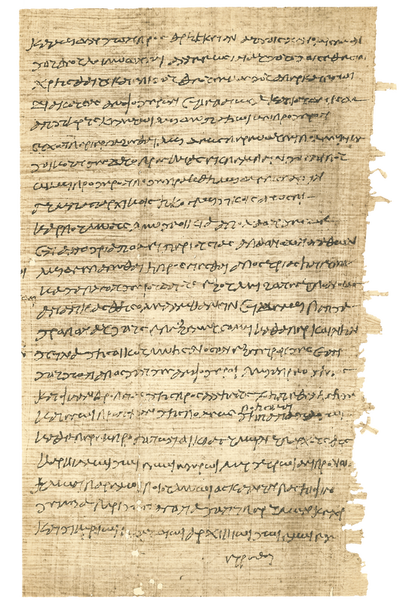

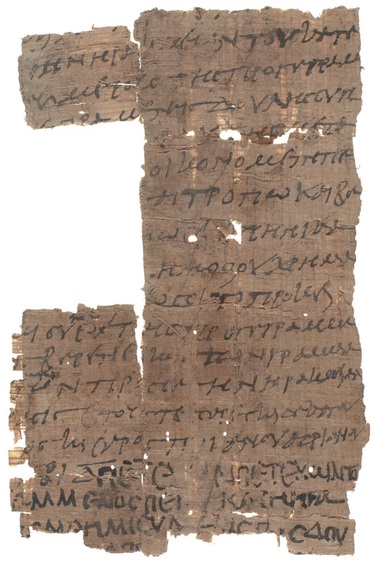

In 1913-1914, English papyrologist John de Monins Johnson excavated the Egyptian city of Antinooupolis on behalf of the Egyptian Exploration Society. Antinooupolis (Ἀντινόου πόλις) was founded as a Greek polis by emperor Hadrian in 130 CE in honour of his friend Antinoos, who is said to have drowned nearby in the Nile. Johnson was on a hunt for papyri and papyri he did find. Many of these unearthed papyri were published in the three-part Antinoopolis Papyri series in the 1950s and 1960s, although the famous "Antinoe Theocritus" papyrus was published in 1930.

In addition to papyri, these excavations yielded other objects such as coins, textiles, hairpins, and metal tools that have been given almost no attention. Included among these "lesser" finds were two socks made of wool, now housed in the British Museum:

In addition to papyri, these excavations yielded other objects such as coins, textiles, hairpins, and metal tools that have been given almost no attention. Included among these "lesser" finds were two socks made of wool, now housed in the British Museum:

Sock no. 1 above would have been worn by an adult on his or her right foot. There is a separation between the big toe and four other toes. This sock is made of wool and has been radiocarbon dated to 100-350 CE. One interesting thing to note is that the impression of the sandal thong is still visible!

Sock no. 2 above is a child's left-foot sock, and the obvious distinction from sock no. 1 is that it is made of 6-7 different colors. Like sock no. 1, this sock separates the big toe from the other four and is made of wool. This one is a little more intricate in design (click to enlarge). It has been radiocarbon dated to 200-400 CE.

So, did the ancient Egyptians wear socks? Of course they did. Simple objects like these two socks give us a glimpse into how ancient people lived their lives. And while Johnson and others were apparently not very interested in these "minor" finds, they are now being studied as part of a collaborative project called Antinoupolis at the British Museum, which is being led by Elisabeth R. O'Connell, Assistant Keeper (Curator) in the Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan with responsibility for Roman and Late Antique collections. This project will make available unpublished objects from Johnson's 1913-1914 excavations, as well as Johnson's unpublished excavation documentation. So, be on the lookout for more textiles, shoes, lamps, coins, figures, and—my favourite—a wooden clapper!

Sock no. 2 above is a child's left-foot sock, and the obvious distinction from sock no. 1 is that it is made of 6-7 different colors. Like sock no. 1, this sock separates the big toe from the other four and is made of wool. This one is a little more intricate in design (click to enlarge). It has been radiocarbon dated to 200-400 CE.

So, did the ancient Egyptians wear socks? Of course they did. Simple objects like these two socks give us a glimpse into how ancient people lived their lives. And while Johnson and others were apparently not very interested in these "minor" finds, they are now being studied as part of a collaborative project called Antinoupolis at the British Museum, which is being led by Elisabeth R. O'Connell, Assistant Keeper (Curator) in the Department of Ancient Egypt and Sudan with responsibility for Roman and Late Antique collections. This project will make available unpublished objects from Johnson's 1913-1914 excavations, as well as Johnson's unpublished excavation documentation. So, be on the lookout for more textiles, shoes, lamps, coins, figures, and—my favourite—a wooden clapper!