AnneMarie Luijendijk. Forbidden Oracles? The Gospel of the Lots of Mary. STAC 89. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014. Xii + 208. Paperback. €69.

I would like to express my utmost appreciation to the kind folks at Mohr Siebeck for sending me a review copy of this book.

This book introduces a fascinating Coptic miniature codex consisting of thirty-seven sortes or oracles. In other words, this is a codex that was used for divinatory purposes. The parchment codex is housed in Harvard University’s Sackler museum where it has been kept since 1984, when Beatrice Kelekian donated it to the museum in memory of her husband, Charles Dikran Kelekian. The book is divided into two main parts. Part 2 is the actual publication of the manuscript, consisting of text, translation, notes, and images. Part 1 consists of four chapters that may be summarized as follows.

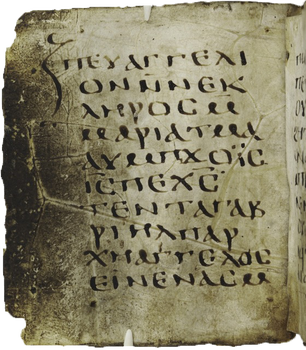

Chapter 1 (“The Gospel of the Lots of Mary”) introduces the codex generally by looking at its incipit and the characters that figure in it. The incipit (pictured above) reads: “The Gospel of the lots of Mary, the mother of the Lord Jesus Christ, she to whom Gabriel the archangel brought the good news. He who will go forward with his whole heart will obtain what he seeks. Only do not be of two minds.” The reference to “lots” (κλῆρος) indicates that the text has something to do with sortilege or divination. Luijendijk argues that “gospel” is a problematic term with respect to how we should understand this text, since it does not read like other gospels, canonical or non-canonical. For example, it only mentions Jesus a few times and has nothing to do with his death or resurrection. According to Luijendijk, the text was identified as a gospel in order to legitimize its contents. Mary, Jesus, and Gabriel were also mentioned in the opening page to “create an atmosphere of awe and trustworthiness” (p. 25).

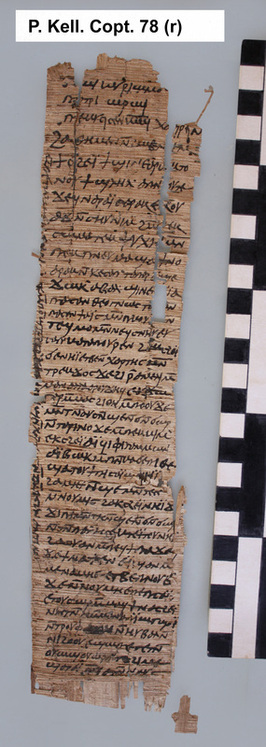

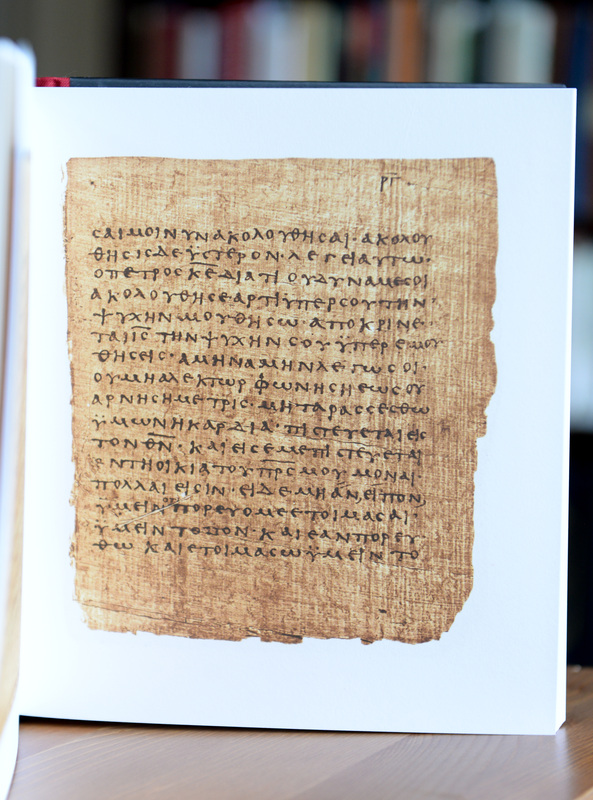

Chapter 2 ("Encountering a Miniature Divination Codex") deals with codicology, palaeography, provenance, and miniature codices. The codex is made up of eighty parchment leaves and is written in a well-trained hand in the Sahidic dialect. Luijendijk dates it to the 5th-6th century on the basis of the handwriting. Each oracle is introduced by a coronis and ends with a series of obeloi (see the image below). The parchment was not lined, but the scribe did a pretty good job at keeping his/her lines and margins straight. The provenance of the codex is not secure, but Luijendijk claims that it may have come from the ancient Egyptian city of Antinoë. Specifically, Luijendijk suggests that the codex stems from the Shrine of St. Colluthus in Antinoë, where archaeologists have discovered many other oracular texts. She repeats the suggested provenance throughout the book, e.g., on p. 90: “Our little codex…was conceivably also used at a martyr’s shrine.” However, other than the fact that many oracular texts have been discovered at this site, nothing else specifically ties the codex to Antinoë. Luijendijk suggests that the “miniature” format may have been prompted by 1) the need to conceal its problematic contents, 2) the economics of production, 3) and/or convenience for travel. She also suggests that the miniature format lent a heightened intimacy and mysterious atmosphere to the divinatory session (p. 53). I found the last explanation least persuasive, since it is difficult to imagine how a somewhat larger codex could not also invite an intimate and "mysterious" atmosphere, however we might imagine these descriptions.

Chapter 3 (“A Three-Way Conversation: Book, Diviner, and Client”) puts this codex in its socio-religious context: sortilege. Luijendijk here explains the various methods of sortilege by looking at the Sortes Astrampsychi, medieval Sortes Sanctorum, and the Jewish “Books of Destiny” (or Goralot). Luijendijk argues that, with respect to our codex, we cannot know for certain how various oracles were chosen during consultation with a diviner. But she ultimately suggests that the method may have been bibliomancy: the practice of randomly opening a biblical book and taking it as a directive for one’s life. She compares the examples of the conversions of Antony and Augustine, who both converted after they randomly heard and read, respectively, passages from the Bible. This hypothesis that our codex was used in this way is certainly possible, although we have no way to confirm it. The rest of this chapter gives the socio-historical Hintergrund: Who sought such oracles? Why? Where did they go to consult an oracle? How did it work? And so on. It seems there is ample evidence that people visited oracles at shrines for health reasons, but the new codex reflects another social reality of clients: safety. For example, Oracle 8 reads: “Fight for yourself in what has happened to you, because it is a human evil. Your enemies are not far from you. They have plotted against you again due to the evil that is in their hearts. But trust in God and walk in his commandments forever.”

Chapter 4 (“A New Voice in the Discourse on Divination”) is broader in nature: it examines the ecclesiastical anxieties about the practice of divination by looking at what certain church authorities said about it. For example, Luijendijk shows that, for Athanasius, the issue was authority. That is to say, Athanasius viewed oracular activity as a threat to the true authority that was given by God to the rightly appointed people. In point of fact, this critique of authority may have been launched at individuals within the clergy. If so, this was a fight between bishops and lower (local) clergy, who were inclined to participate in divination for authority or their own financial gain (clients did, after all, pay the ritual specialist for his/her services). Luijendijk concludes that, although we cannot identify the ritual specialist who used this codex, “he was most likely a priest active at a martyr shrine” (p. 91). In other words, divinatory artifacts such as the new codex reflect a social reality that conflicts with church leaders’ prohibition against such practices. Amulets provide another (related) example: church leaders threatened clergy and non-clergy alike with excommunication if they used them; but they did it anyway.

In Part 2, Luijendijk provides the Coptic text and an English translation of each oracle. Below each English translation one finds brief notes that refer the reader to related passages in the codex, as well as outside of it. Parallel and related passages cited in the notes are provided in Coptic and/or Greek with accompanying English translations. In the following section, black and white images of each page of the codex are provided. Each page is identified by pagination numbers as well as the oracle number.

Conclusion

This book offers a stimulating discussion of an interesting Coptic miniature divinatory codex. It also provides a very accessible introduction to the practice of divination in late antique Christianity generally, a topic which has not been given the attention that it probably deserves. As Luijendijk notes, “The fact that ecclesiastical leaders forbade these oracular practices has probably contributed to relatively little attention scholars have traditionally paid to this genre, as it still remains an understudied topic“ (p. 79). However, Luijendijk has succeeded in showing the relevance of such practices for the study of early Christianity. It is a superb book that should be required reading for all scholars of early Christianity. I warmly recommend it.

I would like to express my utmost appreciation to the kind folks at Mohr Siebeck for sending me a review copy of this book.

This book introduces a fascinating Coptic miniature codex consisting of thirty-seven sortes or oracles. In other words, this is a codex that was used for divinatory purposes. The parchment codex is housed in Harvard University’s Sackler museum where it has been kept since 1984, when Beatrice Kelekian donated it to the museum in memory of her husband, Charles Dikran Kelekian. The book is divided into two main parts. Part 2 is the actual publication of the manuscript, consisting of text, translation, notes, and images. Part 1 consists of four chapters that may be summarized as follows.

Chapter 1 (“The Gospel of the Lots of Mary”) introduces the codex generally by looking at its incipit and the characters that figure in it. The incipit (pictured above) reads: “The Gospel of the lots of Mary, the mother of the Lord Jesus Christ, she to whom Gabriel the archangel brought the good news. He who will go forward with his whole heart will obtain what he seeks. Only do not be of two minds.” The reference to “lots” (κλῆρος) indicates that the text has something to do with sortilege or divination. Luijendijk argues that “gospel” is a problematic term with respect to how we should understand this text, since it does not read like other gospels, canonical or non-canonical. For example, it only mentions Jesus a few times and has nothing to do with his death or resurrection. According to Luijendijk, the text was identified as a gospel in order to legitimize its contents. Mary, Jesus, and Gabriel were also mentioned in the opening page to “create an atmosphere of awe and trustworthiness” (p. 25).

Chapter 2 ("Encountering a Miniature Divination Codex") deals with codicology, palaeography, provenance, and miniature codices. The codex is made up of eighty parchment leaves and is written in a well-trained hand in the Sahidic dialect. Luijendijk dates it to the 5th-6th century on the basis of the handwriting. Each oracle is introduced by a coronis and ends with a series of obeloi (see the image below). The parchment was not lined, but the scribe did a pretty good job at keeping his/her lines and margins straight. The provenance of the codex is not secure, but Luijendijk claims that it may have come from the ancient Egyptian city of Antinoë. Specifically, Luijendijk suggests that the codex stems from the Shrine of St. Colluthus in Antinoë, where archaeologists have discovered many other oracular texts. She repeats the suggested provenance throughout the book, e.g., on p. 90: “Our little codex…was conceivably also used at a martyr’s shrine.” However, other than the fact that many oracular texts have been discovered at this site, nothing else specifically ties the codex to Antinoë. Luijendijk suggests that the “miniature” format may have been prompted by 1) the need to conceal its problematic contents, 2) the economics of production, 3) and/or convenience for travel. She also suggests that the miniature format lent a heightened intimacy and mysterious atmosphere to the divinatory session (p. 53). I found the last explanation least persuasive, since it is difficult to imagine how a somewhat larger codex could not also invite an intimate and "mysterious" atmosphere, however we might imagine these descriptions.

Chapter 3 (“A Three-Way Conversation: Book, Diviner, and Client”) puts this codex in its socio-religious context: sortilege. Luijendijk here explains the various methods of sortilege by looking at the Sortes Astrampsychi, medieval Sortes Sanctorum, and the Jewish “Books of Destiny” (or Goralot). Luijendijk argues that, with respect to our codex, we cannot know for certain how various oracles were chosen during consultation with a diviner. But she ultimately suggests that the method may have been bibliomancy: the practice of randomly opening a biblical book and taking it as a directive for one’s life. She compares the examples of the conversions of Antony and Augustine, who both converted after they randomly heard and read, respectively, passages from the Bible. This hypothesis that our codex was used in this way is certainly possible, although we have no way to confirm it. The rest of this chapter gives the socio-historical Hintergrund: Who sought such oracles? Why? Where did they go to consult an oracle? How did it work? And so on. It seems there is ample evidence that people visited oracles at shrines for health reasons, but the new codex reflects another social reality of clients: safety. For example, Oracle 8 reads: “Fight for yourself in what has happened to you, because it is a human evil. Your enemies are not far from you. They have plotted against you again due to the evil that is in their hearts. But trust in God and walk in his commandments forever.”

Chapter 4 (“A New Voice in the Discourse on Divination”) is broader in nature: it examines the ecclesiastical anxieties about the practice of divination by looking at what certain church authorities said about it. For example, Luijendijk shows that, for Athanasius, the issue was authority. That is to say, Athanasius viewed oracular activity as a threat to the true authority that was given by God to the rightly appointed people. In point of fact, this critique of authority may have been launched at individuals within the clergy. If so, this was a fight between bishops and lower (local) clergy, who were inclined to participate in divination for authority or their own financial gain (clients did, after all, pay the ritual specialist for his/her services). Luijendijk concludes that, although we cannot identify the ritual specialist who used this codex, “he was most likely a priest active at a martyr shrine” (p. 91). In other words, divinatory artifacts such as the new codex reflect a social reality that conflicts with church leaders’ prohibition against such practices. Amulets provide another (related) example: church leaders threatened clergy and non-clergy alike with excommunication if they used them; but they did it anyway.

In Part 2, Luijendijk provides the Coptic text and an English translation of each oracle. Below each English translation one finds brief notes that refer the reader to related passages in the codex, as well as outside of it. Parallel and related passages cited in the notes are provided in Coptic and/or Greek with accompanying English translations. In the following section, black and white images of each page of the codex are provided. Each page is identified by pagination numbers as well as the oracle number.

Conclusion

This book offers a stimulating discussion of an interesting Coptic miniature divinatory codex. It also provides a very accessible introduction to the practice of divination in late antique Christianity generally, a topic which has not been given the attention that it probably deserves. As Luijendijk notes, “The fact that ecclesiastical leaders forbade these oracular practices has probably contributed to relatively little attention scholars have traditionally paid to this genre, as it still remains an understudied topic“ (p. 79). However, Luijendijk has succeeded in showing the relevance of such practices for the study of early Christianity. It is a superb book that should be required reading for all scholars of early Christianity. I warmly recommend it.