I would like to express my utmost appreciation to the kind folks at Oxbow Books for sending me a review copy of this book.

I am very delighted to bring forth a review of this fine volume that is the culmination of over twenty years of work. This second volume completes the publication of Coptic documentary texts discovered at ancient Kellis during excavations from the late 1980s and early 1990s; volume one (P.Kellis V) was published in 1999. It is a continuation of the Dakhleh Oasis Project (DOP), in whose monograph series the volume under review is number sixteen. “The two volumes together present much the largest quantity of Coptic documents dated prior to 400 C.E. to have ever been made available to modern scholarship” (p. 4).

Ancient Kellis was a thriving village in Upper Egypt in the Dakhleh Oasis—one of the seven oases of Egypt’s Western desert. The village was abandoned by 400 C.E., but its literary remains have afforded us the opportunity to understand the lives of the ordinary people who lived there. Almost all of the Greek and Coptic texts were discovered during the excavations of four houses, most of them stemming from House 3, although a few scattered fragments were recovered from the old Tutu Temple area. Klaas Worp’s publication of the Greek texts from Kellis (P.Kellis I) offered valuable insight into the relationships of persons mentioned in the documents, such that Worp was able to construct a genealogical stemma. It is clear that the Greek and Coptic documents from Kellis must be read together, since some of the Greek documents “were written by or for or sent to the very same persons as in the Coptic letters and business accounts” (p. 17).

The Coptic documents in P.Kellis VII are significant for a variety of reasons, some of which may be highlighted briefly here. First, a late 4th century date for the archive is certain. Given the controlled excavations, the archaeological context (stratigraphy, ceramics, coins, etc.) enables us to place these Coptic documents within the time period of c. 355-380+ C.E. (see discussion at p. 6). Thus, their relevance for Coptic palaeography and dating (among other things) cannot be overstated.

Second, the new documents offer even further evidence of the influence of Manichaeism on the inhabitants of Kellis. We find explicit expressions of Manichaean faith such as “the God of Truth” (no. 71), “Praise God!” (no. 71), etc. No. 61 is of particular interest in this regard (the authors call it “the prize letter”), since it seems to be an actual letter from the leader of the Manichaean community in Egypt! Here called “The Teacher,” the leader writes “to all the presbyters, my children, my loved ones.” Moreover, the editors believe that Apa Lysimachos mentioned in no. 72 is a “Manichaean elect,” an acolyte who assisted the senior member of the Manichaen community in Egypt, that is, “The Teacher.” These historical details are vastly important for our understanding of Manichaeism in the 4th century.

Third, of the Coptic letters from Kellis, over 40% are either written by or to a woman. In contrast, less than 10% of the Greek letters from Kellis involve a female correspondent. The editors’ comments in this regard are worth repeating: “We think that these figures are significant; and that for this social group in the latter 4th century there is a correlation between Coptic, family, gender and religious expression. It is well known that women are relatively invisible (with important exceptions) in the Greek documentary record from late antique Egypt. However, this is certainly not the case in the Coptic archive discussed here” (p. 14). A possible explanation for the presence of women in these letters is the absence of their husbands, some of whom were away for work or travel. In no. 75, for example, Pegosh is angry that his wife Parthene had not written to him, and so he reminds her that he is out working all for her sake!

On a somewhat related note, it is interesting, but in no way surprising, that no legal or administrative documents were discovered among the Coptic archive. This is starkly contrasted with the Greek documents from Kellis. Thus, the editors are probably right in saying that this “is a clear impression that Coptic was favoured for the personal and the familial” (p. 12).

P.Kellis VII is a fine addition to scholarship and I warmly welcome its appearance. Edited by a “dream team” of Coptologists, this volume—which is quite large—contributes to discussions about an ancient Egyptian village, Manichaeism, prosopography, family life in the Egyptian desert, Coptic language, palaeography, epistolography, and more. The indices (native words, loan words, geographical names, conjugations, subject index) are comprised of fifty-seven pages and are complete. And mention must be made of the supplementary images on the disc, which is included in a sleeve on the back cover. The color images (in addition to the black and white printed plates at the back of the volume) are for the most part high-resolution JPEGs of all the documents edited in the volume. This feature alone justifies the purchase of the book. Unfortunately, a few of the images are out of focus at some places (particularly at one or the other extreme end of the image) and the image of no. 110v is unusable. Otherwise, the images are excellent, and take up only about 560Mb of hard drive space, should one decide to import them to one’s computer for personal use, as this reviewer did. In sum, I congratulate the editors for their hard efforts in bringing forth a work of lasting significance to historians.

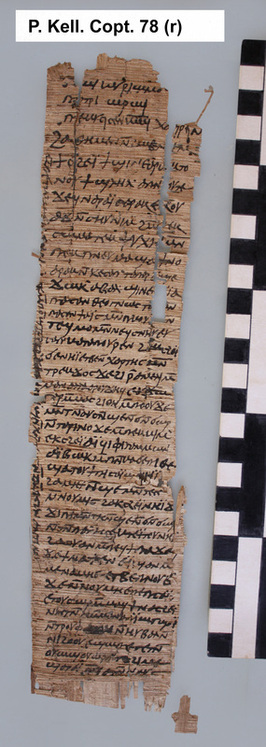

I would like to close the review by reproducing a few lines of the editors’ translation of nos. 78 and 79 (the former is featured on the cover of the book and included below). These letters, written by Pegosh to his father Horos, concern a variety of commodities, including the textile trade. Both letters, however, begin with addressing an interesting matter concerning the purchase of papyrus scrolls, the sum of which is given.

| "Now, you (sg.) have written to me about the papyrus rolls (χάρτης). Do not say that I have been negligent, by no means; but they are expensive! For they have been quoting it—till today—at 1200 talents. When I saw that you did not stop writing (about the papyrus), I took Philammon and went. We did not allow any other inducement until they gave me this pair for 1000 (talents) and 16 nummi." (P.Kellis VII 78.16-27) "Again I am writing to you, telling you about the matter of the papyrus rolls (χάρτης), that I will not neglect (to purchase them); though I have not sent them to you. But, that is I did not send them to you now, for they are expensive. If I hold my hand (for a few more days?); so that, until they ease off (the price?) … they are selling them expensive.” (P.Kellis VII 79.12-19) |