|

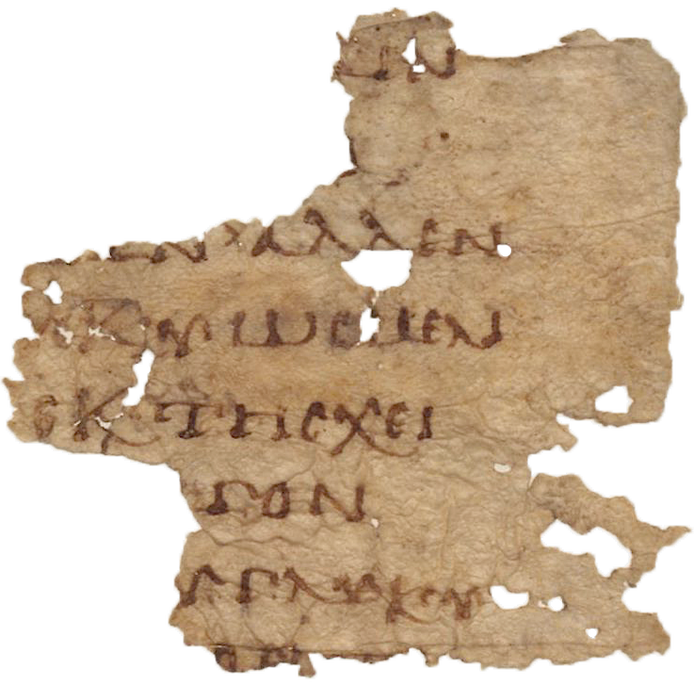

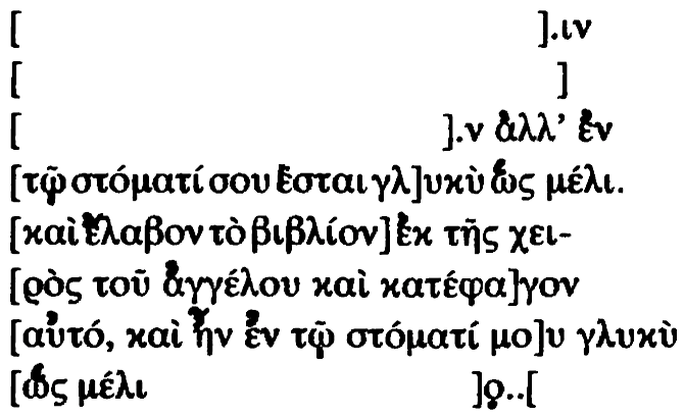

In my book, New Testament Texts on Greek Amulets from Late Antiquity, I briefly drew attention to P.Vindob. G 35894: a small seventh-eighth century parchment fragment containing parts of Revelation 10:9-10 in Greek. Because it is a non-continuous text, it is not formally considered a New Testament manuscript, namely, it is not assigned a Gregory-Aland (GA) number, the numbering system for NT manuscripts. For that reason, it has received almost no attention since its initial publication in 1982. The editor, Uwe Schmidt, observed that the remaining two letters of line 1 (and possibly those of line 8) could not be from Revelation and surmised that the text occupied this single sheet, since the back is blank (i.e., it was likely not from a codex, which contained writing on both sides of the page). As reconstructed, the text has a few variants. Here is an image of the fragment, followed by Schmidt's transcription.  Schmidt said the purpose of the manuscript can only be speculated. He said it could be part of a patristic text in which the biblical portion was being expounded upon, though he found no match. He suggested that it could be an amulet, although there are no Greek amulets with a text of Revelation and "it is difficult to imagine a context for the amulet use of this passage." Finally, he said it could be a school exercise, but opposed this view on account of the neatness of the hand. So, what purpose did this little parchment serve? One might point to the angelic figure mentioned in this passage in support of an amulet designation, since divine beings were frequently invoked or merely listed in amulets. Also, the format is "miniature," typical of amulets. The lack of text on the back side is also a typical feature of amulets. On the other hand, the hand is practiced and the right margin is generous—two rare characteristics of amulets. [Although here it could be argued that the parchment was used secondarily as an amulet. See my discussion of P.Col. 11.293, a fragment from a biblical codex used secondarily as an amulet.] I side with Schmidt here in thinking that the purpose can only be speculated. There are many citations and interpretations of the Apocalypse and other apocalyptica in texts stemming from monastic settings in Egypt. Perhaps it was an amulet. Perhaps it was a little parchment carried around by a monk who liked this particular passage of scripture. Whatever the case, this is one example of many neglected Christian manuscript fragments. So, I leave it here for my readers to ponder!

2 Comments

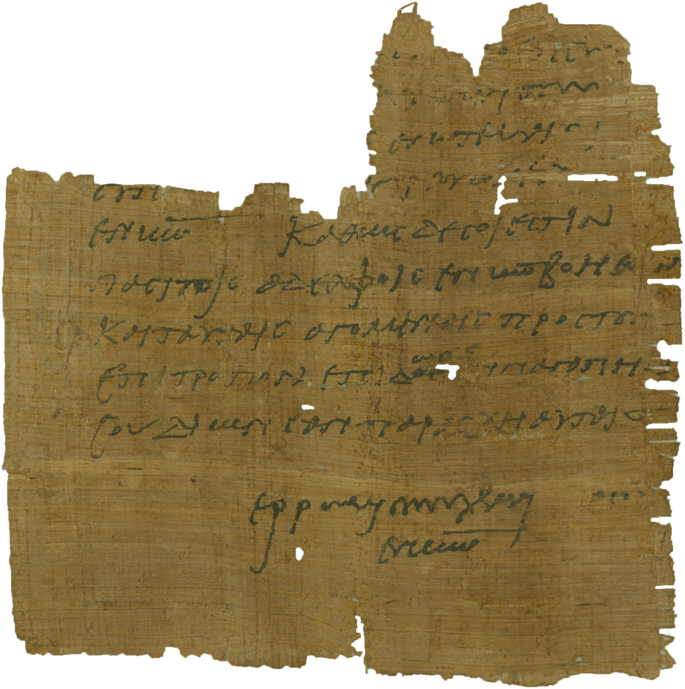

In a third/fourth century Christian Greek papyrus letter, only the ending of which survives, a group of Christians, probably a church, is writing to another Christian or church about a group of women headed their way. These women appear to be in trouble. They are being transported to an epitropos, a "guardian" or "protector." Typically, guardians of women in Greek documents served as legal representatives who assisted them or acted on their behalf in a court of law. It appears, then, that these women were under arrest. It has been suggested that, based on the dating of this papyrus letter, the correspondence may reflect the circumstances of the Roman emperor Diocletian’s persecution of Christians. If that theory is correct—a fact that is not readily demonstrable—then these may have been Christian women who were possibly about to be imprisoned or severely persecuted, perhaps for not denouncing their faith. Before closing the letter, the writer implores the recipient to give his love (agape) to the women as he would to the “brothers.” Here is a translation of the letter followed by the original Greek text and an image of the actual papyrus (P.Got. 11): “I and those with [me] are greeting [you] in (the name of) the Lord. Just as it is your duty to help all the brothers in the name of our Lord, you shall give your love to these (sisters), too, who are being brought to the epitropos, through whatever you will offer them. I wish that you are well in the (name of the) Lord.” [ -ca.?- ] ἐγώ τε κ̣αὶ ο̣ἱ̣ | σὺν [ἐμοί σε προσ]α̣γορεύομ̣ε̣ν̣ | ἐν κ(υρί)ῳ. καθὼς δέ σοί ἐστιν | πᾶσι τοῖς ἀδελφοῖς ἐν κ(υρί)ῳ βοηθ[εῖ]ν | καὶ ταύταις ἀγομέναις πρὸς τὸν ἐπίτροπον ἐπιδ\ώσε̣ι̣ς/ [τ]ὴ̣ν ἀγάπην̣ | σου, διʼ ὧν ἐὰν παράσχῃ αὐταῖς. | ἐρρῶσθαί σε εὔχομαι | ἐν κ(υρί)ῳ. The name “Lord” is abbreviated as a nomen sacrum (“sacred name”), typical of early Christian scribal practice. I think the most interesting part of the request for aid is this statement: “Just as it is your duty to help all the brothers in the name of our Lord, you shall give your love (ἀγάπη) to these (sisters), too.”

“Agape,” or love, was a Christian virtue that became adopted by the earliest communities of believers. The apostle Paul says in his letter to the Galatians, “through love (διὰ τῆς ἀγάπης) become slaves to one another” (5:13). This kind of agape love became a staple of early Christianity and the writer of our papyrus is imploring the recipient to demonstrate his agape to these women in crisis “through what you will offer them.” It is not clear what kind of support the author had in mind and we can only wonder what the ultimate fate of these women was. But, as two scholars have suggested, “the crisis of the women will be one opportunity among many for the exercise of such good-will” (Judge and Pickering, 56). Papyrus letters like this one give us much better insights into the social mobility of Christians, with examples of contact with the State, in a time period in which the Christian church was suffering from persecution. Further reading:

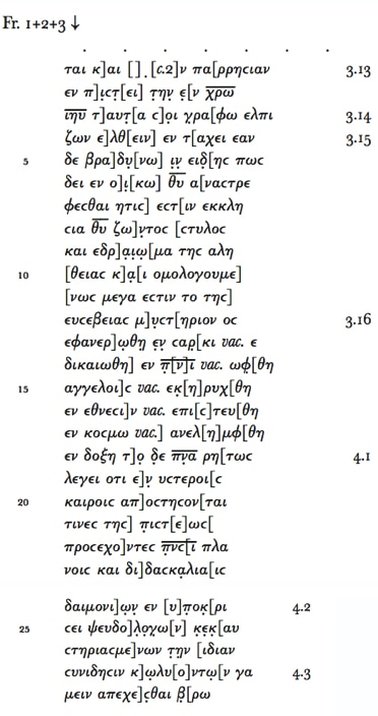

Two new Greek NT papyrus fragments from Oxyrhynchus have been identified: one of Ephesians and one of 1 Timothy. These fragments, already assigned Gregory-Aland numbers, were just published in the latest volume of the Oyrhynchus Papyri--P.Oxy. 81. Dr. Geoff Smith, the author of the Ephesians fragment, has uploaded the editions of both fragments on his Academia.edu site. (Side note: Geoff and I were both featured in a New York Times piece in 2015.) 1. P.Oxy. 81.5258: Ephesians 3:21–4:2, 14-16 / GA P132 Editor: Dr. Geoff Smith A small codex fragment of Ephesians dated to the third/fourth century—the first fragment of this work to surface from Oxyrhynchus. Nomina sacra are present. Written in an informal hand on both sides of the papyrus. There is only one variant in 3:21 (omission of καί). Here is the editor's transcription of both recto and verso. 2. P.Oxy. 81.5259: 1 Timothy 3:13–4:8 / GA P133 Editor: Jessica Shao A small codex fragment of 1 Timothy dated to the third century written on both sides of the papyrus in a fairly large Biblical majuscule hand. The most significant fact is that 5259 is the earliest witness of 1 Timothy to ever be published. Nomina sacra are present. There are only two variants in 3:13 (τὴν vs. τῇ) and 4:2 (συνίδησιν vs. συνείδησιν. The text also exhibits a previously unattested form of a nomen sacrum in 4:1 (πνσι for πνεῦμασιν). Here is the editor's transcription of both recto and verso. In the same volume, there is another interesting Christian papyrus--"5260: Hymn of the Cross: Amulet?"—that I am probably going to come back to in a later post.

I am excited to announce a forthcoming book on Christian amulets: Theodore de Bruyn, Making Amulets Christian: Artefacts, Scribes, and Contexts (Oxford: OUP, 2017). The book is scheduled for release in late August. As readers of this blog probably know, I have a keen interest in amulets. My first major monograph analyzed New Testament citations in Greek amulets and Prof. Theodore de Bruyn's work is cited many, many times. His scholarship speaks for itself. Prof. de Bruyn was kind enough to read several portions of my doctoral dissertation and to answer many questions along the way. Needless to say, this is a book that has been needed for a long time. Amulets have popped up in early Christian studies here and there, but they have largely been ignored, in my opinion. There are so many interesting questions related to the production of amulets, including scribal activities, ritual and social practices, transmission of scripture, Christian symbols, adaptations, "magic," liturgical influences, "syncretism," use by women, etc. I am currently beginning to write an article on the reception of Jesus and Jesus traditions in Christian amulets, an avenue that has not been explored at all. So, I'm very glad to see that amulets are beginning to draw more and more attention by early Christian scholars. I think part of the reason for this is that more and more amulets continue to be identified and published. (I am working together with a colleague on a very interesting papyrus amulet that should be published within a year so stay tuned!) A broad historical study of Christian amulets has been needed, and now that need has been met with the publication of this monograph. Note: The papyrus on the cover is P.Oslo 1.5, a fourth/fifth century Greek amulet against scorpions, snakes, demons, witchcraft, and every kind of evil in a house, with "magical" and Christian characters. I briefly describe it on p. 31 of my book. [The following is taken from Oxford University Press' website] DESCRIPTION Making Amulets Christian: Artefacts, Scribes, and Contexts examines Greek amulets with Christian elements from late antique Egypt in order to discern the processes whereby a customary practice--the writing of incantations on amulets--changed in an increasingly Christian context. It considers how the formulation of incantations and amulets changed as the Christian church became the prevailing religious institution in Egypt in the last centuries of the Roman empire. Theodore de Bruyn investigates what we can learn from incantations and amulets containing Christian elements about the cultural and social location of the people who wrote them. He shows how incantations and amulets were indebted to rituals or ritualizing behavior of Christians. This study analyzes different types of amulets and the ways in which they incorporate Christian elements. By comparing the formulation and writing of individual amulets that are similar to one another, one can observe differences in the culture of the scribes of these materials. It argues for 'conditioned individuality' in the production of amulets. On the one hand, amulets manifest qualities that reflect the training and culture of the individual writer. On the other hand, amulets reveal that individual writers were shaped, whether consciously or inadvertently, by the resources they drew upon-by what is called 'tradition' in the field of religious studies. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Abbreviations A Note on References Introduction 1. Normative Christian Discourse 2. Materials, Format, and Writing 3. Manuals of Procedures and Incantations 4. Scribal Features of Customary Amulets 5. Scribal Features of Scriptural Amulets 6. Christian Ritual Contexts Conclusion Bibliography |

Available at Amazon!

Archives

June 2020

Categories

All

|