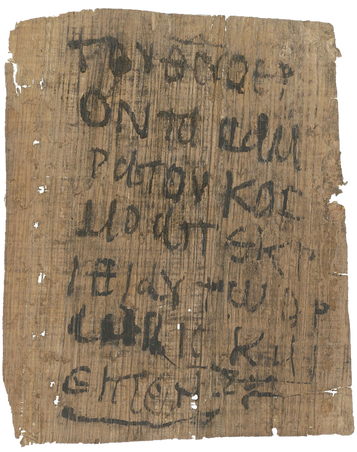

P.Berl. inv. 11710 P.Berl. inv. 11710 In the concluding chapter of my book on Christian amulets, I briefly discuss an identifiable pattern in the corpus of Greek amulets under investigation: nomina sacra (abbreviated sacred names) were written oddly at times and they are frequently written out in full form (i.e., not abbreviated). I gave a few examples in that dicussion: ερ for σῶτερ χ for χριστός θου for θεοῦ (see image at left) κ for κυρίω I have recently accepted an invitation to contribute a chapter to an edited monograph to be published by Brill, and my plan is to address the question that I left unanswered in my book: “Why was such a well-established Christian scribal convention altered in many paraliterary texts?” Here is a working abstract: Over the last century, the Christian scribal practice of abbreviating sacred names (nomina sacra) has received ample attention. Their presence in our earliest Christian material evidence suggests that this scribal phenomenon developed early on and may have spread widely within Christian circles. It is a generally held view that nomina sacra within a written document are markers of Christianity. While some irregularities in the writing of these names have been noted, the most common sacred names (i.e., God, Jesus, Lord, Christ) are abbreviated with a high degree of consistency in Christian manuscripts. However, when we turn to certain genres, like amulets and private letters, nomina sacra frequently exhibit idiosyncrasies and inconsistencies. For example, we find odd forms of abbreviation, and sometimes the nomina sacra exhibit scriptio plena (i.e., spelled in full) where one would expect abbreviated forms. Given the abundance of these “errors” (as they have usually been classified) and inconsistencies in the writing of nomina sacra outside biblical and other Christian literary texts, it prompts the question: why was such a well-established scribal convention altered in many paraliterary texts? This chapter explores this question by looking at specific cases within Christian amulets. The study then considers these texts within the context of “magic,” monasticism, private reading, and Christian ritual practices to see how Christian scribal habits may have been affected. The question the study poses is challenging, because when you start to think about an answer, you realize that there are all sorts of related, complicated questions. For example, who wrote “Christian” amulets? There are many possibilities: clergy, monks, priests, ritual experts (secular/Christian?), individuals who used amulets, and so on. To what extent were they aware of the Christian convention of abbreviating sacred names? And were they copying from memory or an exemplar? If they were copying a text in front of them, did these copyists understand the “system” they were carrying over into their text? How many of these amulets were actually read? Some were obviously folded and worn on the body, probably after an initial ritual. Many of these were surely never unfolded and read. Some are more likely candidates to have be used more than once. In those cases, who was reading them and how well could they read? Would the readers have understood the nomina sacra? Might the quality of scripts correspond to the care given to things like abbreviations, punctuation, textual character and the like? All of these questions are relevant for the question driving the study. A tempting answer would be to say that these are private and ephemeral documents written by careless scribes, which explains why amulets exhibit so many idiosyncrasies. That’s typically the answer one encounters. And this may indeed be true to some extent. But are there other ways to approach the question? I welcome the thoughts and suggestions of others here.

7 Comments

|

Available at Amazon!

Archives

June 2020

Categories

All

|