0 Comments

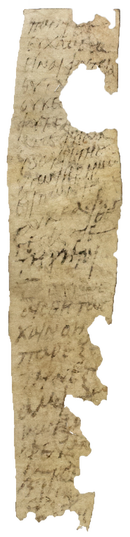

P.Monts. Roca 4.57

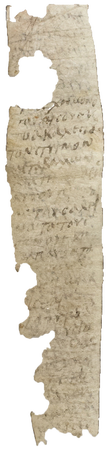

Methodius of Olympus was a Christian bishop who died as a martyr in c. 311 C.E. Unfortunately, we know very little about Methodius. Most of what we do know comes from a brief biographical account in Jerome’s On Illustrious Men, which was composed at the end of the fourth century. Methodius was mainly known as an antagonist of Origen. In particular, he had a problem with Origen’s doctrine of the resurrection of the body, which he rejects outright in his treatise On the Resurrection. Methodius wrote several important works (see Roger Pearse’s list here), but almost all of these come down to us in fragmentary form. The only complete work of Methodius that we possess is his Symposium or Banquet—a treatise in praise of voluntary virginity. Until quite recently, the earliest manuscript of this text was an eleventh century codex known as Patmiacus Graecus 202, which is housed in the Monastery of St. John the Theologian on the island of Patmos. But a remarkable discovery has recently been made in the Montserrat Abbey in Spain. Sofia Torallas Tovar and Klaas A. Worp, who have been working on the manuscript collection in the Montserrat Abbey for many years, have just published a fragment of Methodius’ Symposium that they date on palaeographical grounds to the fifth-sixth century—about 450 years earlier than the Patmos codex mentioned above. (On another recent, important discovery by Tovar and Worp, see here.) Published as P.Monts. Roca 4.57, this fragment is the first attestation of a work of Methodius from Egypt. It is a narrow strip of parchment, with thirty partial lines preserved on the hair side (see image of fragment at right). The text on this side of the fragment comes from Oratio 8:16.72-73, 3:14.35-40, 8.60-61, and 9.18-19 (in that order). The flesh side contains thirty-five partial lines of text unrelated to the Methodian text. This is an unidentified Christian text with “Gnomic” sentiments, as the authors explain. In addition to the wonderful fact that we now have a significantly earlier manuscript witness of Methodius’ text, there is also another remarkable feature in the new manuscript: a previously unattested saying about the Nile. In lines 5-8, the manuscript reads: “The rise of the Nile is life and joy for the families” ἡ ἀνάβα̣σ̣ε̣ι̣[ς] τοῦ Νείλου̣ ζω̣ή̣ ἐστι κ̣[αὶ] χαρὰ ἑστία[ις] As the authors note, this saying does not occur in Methodius. And indeed, it does not fit the immediate context. Where it comes from is a mystery, but the saying is nonetheless very interesting. All in all, this is a fascinating discovery for scholars of Early Christianity and we commend the authors for their editorial work in making this text available to the world. An interesting little parchment fragment kept in the Montserrat Abbey in Spain has just been published in Sofía Torallas Tovar and Klaas A. Worp, ed., with the collaboration of Alberto Nodar and María Victoria Spottorno, Greek Papyri from Montserrat (P.Monts. Roca IV) (Barcelona: 2014). I will say more about this excellent volume at a later time, but I wanted to comment on one of the fragments published therein for the first time. P.Monts.Roca 4.59 is a Christian Greek text of unknown nature. The editors tentatively date it to the fifth/sixth century on palaeographical grounds. It is oblong and written in a fairly well-trained hand. Both sides are inscribed; there are traces of another text on the hair side, so presumably it is a palimpsest. The text is certainly Christian, but it is difficult to know precisely what kind of text we are dealing with. Some of the phrases are similar to phrases found in several homiletic texts (e.g., Cyril, Chrysostom, and Didymus), so a homily is at least a good possibility. In any case, perhaps the most interesting feature of the text is that it contains a new saying attributed to Jesus. In other words, it is an agraphon: a saying of Jesus that is not found in the canonical gospels. The saying is in bold in the text reproduced below. The text that comes immediately before the saying seems to have been influenced by Matt. 15:13/Is. 61:3 LXX. The "plantation of God" is probably just a metaphor for "the people of God." But what does it mean for the plantation of God to be "retained to pronounce sweet words?" The editors point to a similar phrase in Diodorus' Comm. Ps. 49.19b, but that is equally obscure. All the same, the saying is a nice little addition to the agrapha and we are indebted to Torallas Tovar and Worp for bringing this little fragment to our attention.

In the latest issue of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri series (LXXVIII, Egyptian Exploration Society, 2012), W. B. Henry offers an edition of P.Oxy. 5129 (Justin Martyr's First Apology), which is the earliest Greek manuscript of any text of Justin Martyr. According to Henry, "[t]his is the first published ancient copy of a work of Justin Martyr. The text is otherwise known only from the unreliable manuscript A (Parisinus graecus 450, of 1364)." Henry dates the hand to the 4th century CE, citing P.Oxy. 2699 and P.Herm. 5 as comparanda. This is, therefore, an incredible discovery, since P.Oxy. 5129 predates the earliest manuscript of Justin by a millennium! There are a few variants in the fragment (e.g., omission of εντυχειν in 50.12, υμων instead of ημων in 51.4) that make the text important for text-critical study of Justin's First Apology. The manuscript is written on parchment in an elegant hand of the "Severe" type. Unfortunately, only six, partial lines have been preserved (3 lines on hair, 3 lines on flesh), and the flesh side is particularly sparse. Henry collates the text with the critical edition of D. Minns and P. Parvis (2009). For interested readers, I reproduce Henry's transcription of the text of P.Oxy. 5129 below, alongside my own translation (with brackets signifying reconstructions), which is followed by a snapshot of the hair side of the fragment.

|

Available at Amazon!

Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|